- Home

- J. K. Rowling

The Half-Blood Prince

The Half-Blood Prince Read online

HARRY

POTTER

and the Half-Blood Prince

J.K. ROWLING

All rights reserved; no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher

This digital edition first published by Pottermore Limited in 2012

First published in print in Great Britain in 2005 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Copyright © J.K. Rowling 2005

Cover illustrations by Claire Melinsky copyright © J.K. Rowling 2010

Harry Potter characters, names and related indicia are trademarks of and © Warner Bros. Ent.

J.K. Rowling has asserted her moral rights

A CIP catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-78110-012-7

www.pottermore.com

by J.K. Rowling

The unique online experience built around the Harry Potter books. Share and participate in the stories, showcase your own Potter-related creativity and discover even more about the world of Harry Potter from the author herself.

Visit pottermore.com

To Mackenzie,

my beautiful daughter,

I dedicate

her ink and paper twin

CONTENTS

ONE

The Other Minister

TWO

Spinner’s End

THREE

Will and Won’t

FOUR

Horace Slughorn

FIVE

An Excess of Phlegm

SIX

Draco’s Detour

SEVEN

The Slug Club

EIGHT

Snape Victorious

NINE

The Half-Blood Prince

TEN

The House of Gaunt

ELEVEN

Hermione’s Helping Hand

TWELVE

Silver and Opals

THIRTEEN

The Secret Riddle

FOURTEEN

Felix Felicis

FIFTEEN

The Unbreakable Vow

SIXTEEN

A Very Frosty Christmas

SEVENTEEN

A Sluggish Memory

EIGHTEEN

Birthday Surprises

NINETEEN

Elf Tails

TWENTY

Lord Voldemort’s Request

TWENTY-ONE

The Unknowable Room

TWENTY-TWO

After the Burial

TWENTY-THREE

Horcruxes

TWENTY-FOUR

Sectumsempra

TWENTY-FIVE

The Seer Overheard

TWENTY-SIX

The Cave

TWENTY-SEVEN

The Lightning-Struck Tower

TWENTY-EIGHT

Flight of the Prince

TWENTY-NINE

The Phoenix Lament

THIRTY

The White Tomb

— CHAPTER ONE —

The Other Minister

It was nearing midnight and the Prime Minister was sitting alone in his office, reading a long memo that was slipping through his brain without leaving the slightest trace of meaning behind. He was waiting for a call from the president of a far-distant country, and between wondering when the wretched man would telephone, and trying to suppress unpleasant memories of what had been a very long, tiring and difficult week, there was not much space in his head for anything else. The more he attempted to focus on the print on the page before him, the more clearly the Prime Minister could see the gloating face of one of his political opponents. This particular opponent had appeared on the news that very day, not only to enumerate all the terrible things that had happened in the last week (as though anyone needed reminding) but also to explain why each and every one of them was the government’s fault.

The Prime Minister’s pulse quickened at the very thought of these accusations, for they were neither fair nor true. How on earth was his government supposed to have stopped that bridge collapsing? It was outrageous for anybody to suggest that they were not spending enough on bridges. The bridge was less than ten years old, and the best experts were at a loss to explain why it had snapped cleanly in two, sending a dozen cars into the watery depths of the river below. And how dared anyone suggest that it was lack of policemen that had resulted in those two very nasty and well-publicised murders? Or that the government should have somehow foreseen the freak hurricane in the West Country that had caused so much damage to both people and property? And was it his fault that one of his Junior Ministers, Herbert Chorley, had chosen this week to act so peculiarly that he was now going to be spending a lot more time with his family?

‘A grim mood has gripped the country,’ the opponent had concluded, barely concealing his own broad grin.

And unfortunately, this was perfectly true. The Prime Minister felt it himself; people really did seem more miserable than usual. Even the weather was dismal; all this chilly mist in the middle of July … it wasn’t right, it wasn’t normal …

He turned over the second page of the memo, saw how much longer it went on, and gave it up as a bad job. Stretching his arms above his head he looked around his office mournfully. It was a handsome room, with a fine marble fireplace facing the long sash windows, firmly closed against the unseasonable chill. With a slight shiver, the Prime Minister got up and moved over to the windows, looking out at the thin mist that was pressing itself against the glass. It was then, as he stood with his back to the room, that he heard a soft cough behind him.

He froze, nose-to-nose with his own scared-looking reflection in the dark glass. He knew that cough. He had heard it before. He turned, very slowly, to face the empty room.

‘Hello?’ he said, trying to sound braver than he felt.

For a brief moment he allowed himself the impossible hope that nobody would answer him. However, a voice responded at once, a crisp, decisive voice that sounded as though it were reading a prepared statement. It was coming – as the Prime Minister had known at the first cough – from the froglike little man wearing a long silver wig who was depicted in a small and dirty oil-painting in the far corner of the room.

‘To the Prime Minister of Muggles. Urgent we meet. Kindly respond immediately. Sincerely, Fudge.’ The man in the painting looked enquiringly at the Prime Minister.

‘Er,’ said the Prime Minister, ‘listen … it’s not a very good time for me … I’m waiting for a telephone call, you see … from the president of –’

‘That can be rearranged,’ said the portrait at once. The Prime Minister’s heart sank. He had been afraid of that.

‘But I really was rather hoping to speak –’

‘We shall arrange for the president to forget to call. He will telephone tomorrow night instead,’ said the little man. ‘Kindly respond immediately to Mr Fudge.’

‘I … oh … very well,’ said the Prime Minister weakly. ‘Yes, I’ll see Fudge.’

He hurried back to his desk, straightening his tie as he went. He had barely resumed his seat, and arranged his face into what he hoped was a relaxed and unfazed expression, when bright green flames burst into life in the empty grate beneath his marble mantelpiece. He watched, trying not to betray a flicker of surprise or alarm, as a portly man appeared within the flames, spinning as fast as a top. Seconds later, he had climbed out on to a rather fine antique rug, brushing ash from the sleeves of his long pinstriped cloak, a lime-green bowler hat in his hand.

‘Ah … Prime Minister,’ said Cornelius Fudge, striding forwards with his hand outstretched. ‘Good to see you again.’

The Prime Ministe

r could not honestly return this compliment, so said nothing at all. He was not remotely pleased to see Fudge, whose occasional appearances, apart from being downright alarming in themselves, generally meant that he was about to hear some very bad news. Furthermore, Fudge was looking distinctly careworn. He was thinner, balder and greyer, and his face had a crumpled look. The Prime Minister had seen that kind of look in politicians before, and it never boded well.

‘How can I help you?’ he said, shaking Fudge’s hand very briefly and gesturing towards the hardest of the chairs in front of the desk.

‘Difficult to know where to begin,’ muttered Fudge, pulling up the chair, sitting down and placing his green bowler upon his knees. ‘What a week, what a week …’

‘Had a bad one too, have you?’ asked the Prime Minister stiffly, hoping to convey by this that he had quite enough on his plate already without any extra helpings from Fudge.

‘Yes, of course,’ said Fudge, rubbing his eyes wearily and looking morosely at the Prime Minister. ‘I’ve been having the same week you have, Prime Minister. The Brockdale bridge … the Bones and Vance murders … not to mention the ruckus in the West Country …’

‘You – er – your – I mean to say, some of your people were – were involved in those – those things, were they?’

Fudge fixed the Prime Minister with a rather stern look.

‘Of course they were,’ he said. ‘Surely you’ve realised what’s going on?’

‘I …’ hesitated the Prime Minister.

It was precisely this sort of behaviour that made him dislike Fudge’s visits so much. He was, after all, the Prime Minister, and did not appreciate being made to feel like an ignorant schoolboy. But of course, it had been like this from his very first meeting with Fudge on his very first evening as Prime Minister. He remembered it as though it were yesterday and knew it would haunt him until his dying day.

He had been standing alone in this very office, savouring the triumph that was his after so many years of dreaming and scheming, when he had heard a cough behind him, just like tonight, and turned to find that ugly little portrait talking to him, announcing that the Minister for Magic was about to arrive and introduce himself.

Naturally, he had thought that the long campaign and the strain of the election had caused him to go mad. He had been utterly terrified to find a portrait talking to him, though this had been nothing to how he had felt when a self-proclaimed wizard had bounced out of the fireplace and shaken his hand. He had remained speechless throughout Fudge’s kindly explanation that there were witches and wizards still living in secret all over the world, and his reassurances that he was not to bother his head about them as the Ministry of Magic took responsibility for the whole wizarding community and prevented the non-magical population from getting wind of them. It was, said Fudge, a difficult job that encompassed everything from regulations on responsible use of broomsticks to keeping the dragon population under control (the Prime Minister remembered clutching the desk for support at this point). Fudge had then patted the shoulder of the still-dumbstruck Prime Minister in a fatherly sort of way.

‘Not to worry,’ he had said, ‘it’s odds on you’ll never see me again. I’ll only bother you if there’s something really serious going on our end, something that’s likely to affect the Muggles – the non-magical population, I should say. Otherwise it’s live and let live. And I must say, you’re taking it a lot better than your predecessor. He tried to throw me out of the window, thought I was a hoax planned by the opposition.’

At this, the Prime Minister had found his voice at last.

‘You’re – you’re not a hoax, then?’

It had been his last, desperate hope.

‘No,’ said Fudge gently. ‘No, I’m afraid I’m not. Look.’

And he had turned the Prime Minister’s teacup into a gerbil.

‘But,’ said the Prime Minister breathlessly, watching his teacup chewing on the corner of his next speech, ‘but why – why has nobody told me –?’

‘The Minister for Magic only reveals him or herself to the Muggle Prime Minister of the day,’ said Fudge, poking his wand back inside his jacket. ‘We find it the best way to maintain secrecy.’

‘But then,’ bleated the Prime Minister, ‘why hasn’t a former Prime Minister warned me –?’

At this, Fudge had actually laughed.

‘My dear Prime Minister, are you ever going to tell anybody?’

Still chortling, Fudge had thrown some powder into the fireplace, stepped into the emerald flames and vanished with a whooshing sound. The Prime Minister had stood there, quite motionless, and realised that he would never, as long as he lived, dare mention this encounter to a living soul, for who in the wide world would believe him?

The shock had taken a little while to wear off. For a time he had tried to convince himself that Fudge had indeed been a hallucination brought on by lack of sleep during his gruelling election campaign. In a vain attempt to rid himself of all reminders of this uncomfortable encounter, he had given the gerbil to his delighted niece and instructed his Private Secretary to take down the portrait of the ugly little man who had announced Fudge’s arrival. To the Prime Minister’s dismay, however, the portrait had proved impossible to remove. When several carpenters, a builder or two, an art historian and the Chancellor of the Exchequer had all tried unsuccessfully to prise it from the wall, the Prime Minister had abandoned the attempt and simply resolved to hope that the thing remained motionless and silent for the rest of his term in office. Occasionally he could have sworn he saw out of the corner of his eye the occupant of the painting yawning, or else scratching his nose; even, once or twice, simply walking out of his frame and leaving nothing but a stretch of muddy-brown canvas behind. However, he had trained himself not to look at the picture very much, and always to tell himself firmly that his eyes were playing tricks on him when anything like this happened.

Then, three years ago, on a night very like tonight, the Prime Minister had been alone in his office when the portrait had once again announced the imminent arrival of Fudge, who had burst out of the fireplace, sopping wet and in a state of considerable panic. Before the Prime Minister could ask why he was dripping all over the Axminster, Fudge had started ranting about a prison the Prime Minister had never heard of, a man named ‘Serious’ Black, something that sounded like Hogwarts and a boy called Harry Potter, none of which made the remotest sense to the Prime Minister.

‘… I’ve just come from Azkaban,’ Fudge had panted, tipping a large amount of water out of the rim of his bowler hat into his pocket. ‘Middle of the North Sea, you know, nasty flight … the Dementors are in uproar –’ he shuddered ‘– they’ve never had a breakout before. Anyway, I had to come to you, Prime Minister. Black’s a known Muggle killer and may be planning to rejoin You-Know-Who … but of course, you don’t even know who You-Know-Who is!’ He had gazed hopelessly at the Prime Minister for a moment, then said, ‘Well, sit down, sit down, I’d better fill you in … have a whisky …’

The Prime Minister had rather resented being told to sit down in his own office, let alone offered his own whisky, but he sat nevertheless. Fudge had pulled out his wand, conjured two large glasses full of amber liquid out of thin air, pushed one of them into the Prime Minister’s hand and drawn up a chair.

Fudge had talked for over an hour. At one point, he had refused to say a certain name aloud, and wrote it instead on a piece of parchment, which he had thrust into the Prime Minister’s whisky-free hand. When at last Fudge had stood up to leave, the Prime Minister had stood up too.

‘So you think that …’ he had squinted down at the name in his left hand, ‘Lord Vol—’

‘He Who Must Not Be Named!’ snarled Fudge.

‘I’m sorry … you think that He Who Must Not Be Named is still alive, then?’

‘Well, Dumbledore says he is,’ said Fudge, as he had fastened his pinstriped cloak under his chin, ‘but we’ve never found him. If you ask me, he’s not dan

gerous unless he’s got support, so it’s Black we ought to be worrying about. You’ll put out that warning, then? Excellent. Well, I hope we don’t see each other again, Prime Minister! Goodnight.’

But they had seen each other again. Less than a year later a harassed-looking Fudge had appeared out of thin air in the Cabinet Room to inform the Prime Minister that there had been a spot of bother at the Kwidditch (or that was what it had sounded like) World Cup and that several Muggles had been ‘involved’, but that the Prime Minister was not to worry, the fact that You-Know-Who’s Mark had been seen again meant nothing; Fudge was sure it was an isolated incident and the Muggle Liaison Office was dealing with all memory modifications as they spoke.

‘Oh, and I almost forgot,’ Fudge had added. ‘We’re importing three foreign dragons and a sphinx for the Triwizard Tournament, quite routine, but the Department for the Regulation and Control of Magical Creatures tells me that it’s down in the rulebook that we have to notify you if we’re bringing highly dangerous creatures into the country.’

‘I – what – dragons?’ spluttered the Prime Minister.

‘Yes, three,’ said Fudge. ‘And a sphinx. Well, good day to you.’

The Prime Minister had hoped beyond hope that dragons and sphinxes would be the worst of it, but no. Less than two years later, Fudge had erupted out of the fire yet again, this time with the news that there had been a mass breakout from Azkaban.

‘A mass breakout?’ the Prime Minister had repeated hoarsely.

‘No need to worry, no need to worry!’ Fudge had shouted, already with one foot in the flames. ‘We’ll have them rounded up in no time – just thought you ought to know!’

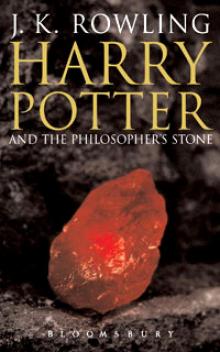

Harry Potter and the Philosophers Stone

Harry Potter and the Philosophers Stone Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets

Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire

Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix

Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince

Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them

Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them Short Stories from Hogwarts of Heroism, Hardship and Dangerous Hobbies

Short Stories from Hogwarts of Heroism, Hardship and Dangerous Hobbies Hogwarts: An Incomplete and Unreliable Guide

Hogwarts: An Incomplete and Unreliable Guide The Tales of Beedle the Bard

The Tales of Beedle the Bard The Casual Vacancy

The Casual Vacancy Harry Potter and the Cursed Child

Harry Potter and the Cursed Child Short Stories from Hogwarts of Power, Politics and Pesky Poltergeists

Short Stories from Hogwarts of Power, Politics and Pesky Poltergeists Quidditch Through the Ages

Quidditch Through the Ages The Ickabog

The Ickabog![Fantastic Beasts, The Crimes of Grindelwald [UK] Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/19/fantastic_beasts_the_crimes_of_grindelwald_uk_preview.jpg) Fantastic Beasts, The Crimes of Grindelwald [UK]

Fantastic Beasts, The Crimes of Grindelwald [UK] Harry Potter and the Cursed Child: Parts One and Two

Harry Potter and the Cursed Child: Parts One and Two The Prisoner of Azkaban

The Prisoner of Azkaban Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald

Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald The Hogwarts Library Collection

The Hogwarts Library Collection Short Stories from Hogwarts of Heroism, Hardship and Dangerous Hobbies (Kindle Single) (Pottermore Presents)

Short Stories from Hogwarts of Heroism, Hardship and Dangerous Hobbies (Kindle Single) (Pottermore Presents) Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows hp-7

Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows hp-7 Hogwarts: An Incomplete and Unreliable Guide (Kindle Single) (Pottermore Presents)

Hogwarts: An Incomplete and Unreliable Guide (Kindle Single) (Pottermore Presents) Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire hp-4

Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire hp-4 The Christmas Pig

The Christmas Pig Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone The Order of the Phoenix

The Order of the Phoenix Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban hp-3

Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban hp-3 Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets hp-2

Harry Potter and the Chamber of Secrets hp-2 HP 3 - Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban

HP 3 - Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban The Half-Blood Prince

The Half-Blood Prince The Hogwarts Collection

The Hogwarts Collection Tales of Beedle the Bard

Tales of Beedle the Bard The Goblet of Fire

The Goblet of Fire Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince hp-6

Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince hp-6 Short Stories from Hogwarts of Power, Politics and Pesky Poltergeists (Kindle Single) (Pottermore Presents)

Short Stories from Hogwarts of Power, Politics and Pesky Poltergeists (Kindle Single) (Pottermore Presents) Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone hp-1

Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone hp-1